When I came to Talbot as a student I was at a crossroads. I knew that I wanted to be in ministry, but I wasn’t sure whether I should pursue a church-based pastoral ministry or an academic one. I was also wrestling with a lot of my own immaturity, sin, and struggles that I couldn’t seem to put aside. I came to seminary with a lot of passion for the things of God, and I imagined that seminary was going to be a place to learn what I needed to thrive wherever God led me. That proved true. But something else proved true as well. Talbot became the place where I discovered a deep formation of heart and mind around God and the things of God that has animated my calling into both the academy and the church.

Not everyone is called to both an academic and a churchly ministry, but as I waffled back and forth it became clear that the only way I could work in the academy was if I was deeply invested in the leadership and preaching of the church. I currently lead my church’s preaching team, having also helped lead as an elder and in other capacities over the past 11 years. It was studying spiritual theology at Talbot that helped me weave together all I had learned in Bible, theology, and philosophy into a cohesive vision of life with God. It wasn’t just knowledge, but a life devoted to the Lord that helped make sense of what faithfulness in ministry actually looks like.

Unfortunately, this isn’t always the standard experience of seminary. Before I came I was warned about going to seminary. The worry was that seminary would be a place where my head would inflate while my heart would wander from God. My experience was the exact opposite. It was at Talbot, and specifically in my spiritual formation classes, that I discovered a training not only in knowledge and skill, but in wisdom and love.

Before we partitioned theology into is various guilds (e.g., New Testament studies, Old Testament studies, systematic theology) and divided the theological task into contrasting methodologies, we used to just talk about divinity (we still do this with the Master of Divinity degree). Theologians used to be called divines for this reason. One of my favorite historic definitions of divinity is simply, “the doc-trine of living for God through Christ” (Petrus van Mastricht, Theoretical-Practical Theology: Volume 1: Prolegomena). In this sense, divinity is not only to be studied but lived. Unfortunately, it is this lived reality of life with God that can so often be left aside, as if the experiential and practical dynamics of Christian growth were somehow not essential to training for ministry.

Talbot’s response to this, nearly 25 years ago, was to center spiritual theology in the curriculum. Spiritual theology, as a discipline, seeks to reintegrate the study of Scripture, theology, and practice around the gospel for life in the body of Christ. In other words, spiritual theology is always pastoral theology. Spiritual theology is always about life with God and helping to shepherd others to God no matter where they are.

This means that the spiritual theologian has to address questions about how the spiritual life differs from things like natural virtue formation. The spiritual theologian cannot stop there, however, for the same reason that the pastor cannot stop at theory. We have to move beyond theory to the actual dynamics of Christian growth. Brought to the foreground are questions like: What does Christian growth feel like? How does God’s action relate to my discipline? What sorts of devotional activities am I called to give myself to? How do I discern God’s will for my life?

Alongside the basic considerations of Chris-tian discernment and spiritual growth is the simple question: What actually is Christian growth? How do we understand growing in holiness? How does my individual growth relate to my role in the church? Is my ministry impacted by my spiritual formation, and if so, in what ways? We have to attend deeply, not only to theory, but to the very questions that animate most of our spiritual lives. We need to wrestle deeply about our own experience with God, and our own presuppositions and temptations, if we are going to be the kinds of people who can shepherd God’s people. This is why the spiritual theologian con-siders how we mature from infancy in Christ into adolescence and then to adulthood, so that we can leave behind milk to consume solid food (1 Cor. 3:2).

After focusing on the nature and processes of spiritual growth, the spiritual theologian addresses what it looks like to actually shepherd a people in light of this. This leads us to consider the directives of Christian growth and what it means in preaching, pastoral care, or things like small groups, focusing on questions like: If someone cannot simply generate supernatural growth, what sorts of directives can we give? If we are living, not under law, but grace, how are spiritual practices “means of grace,” as our tradition used to say? If our ministry cannot be reduced to performance, and if it is true that God’s power is made perfect in our weakness, then what should ministry in the Spirit look like?

As B.B. Warfield reminded seminarians who were under his care, “we should pause to remind ourselves that intellectual training alone will never make a true minister; that the heart has rights which the head must respect; and that it behooves us above every-thing to remember that the ministry is a spiritual office” (B.B. Warfield, “Spiritual Culture in the Theological Seminary” in The Princeton Theological Review 2:1). This leads him to talk about seminary as a kind of “retreat,” precisely because training for the ministry is always a spiritual task. This spiritual task is a “three-ply cord” according to Warfield, one that focuses on the head, heart, and hands (B. B. Warfield, “Spiritual Culture in the Theological Seminary”). When we forget this, or when we trade the spiritual calling of the church for a secular calling, we inevitably trade prayer for performance, wisdom for knowledge, and love for savvy and skill. Or, perhaps, we choose between head, heart, or hands, to the neglect of the others.

It is important never to underestimate the temptation to reduce ministry down to a natural task — a task of knowledge and skill alone — and forget it is a supernatural calling. Our calling will always require knowledge and skill, no doubt, but those things are secondary to the deeper foundation of wisdom and love that are discovered by faith. This is certainly true for the pastorate, but it pervades every ministry of the church. There is nowhere we go to serve in the church that suddenly becomes a natural task. We are never merely cultivating natural skill in the church. We are ministering the presence of God in and from and for the love of God.

As Warfield explained to his incoming seminary students, admonishing them not to focus on their head in such a way that neglects their heart:

True devoutness is a plant that grows best in seclusion and the darkness of the closet; and we cannot reach the springs of our devout life until we penetrate into the sanctuary where the soul meets habitually with its God. Let us then make it our chief concern in our preparation for the ministry to institute between our hearts and God our Maker, Redeemer and Sanctifier such an intimacy of communion that we may realize in our lives the command of Paul to pray without ceasing and in everything to give thanks, and that we may see fulfilled in our own experiences our Lord’s promise not only to enter into our hearts, but unbrokenly to abide in them and to unite them to Himself in an intimacy comparable to the union of the Father and the Son (B. B. Warfield, “Spiritual Culture in the Theological Seminary”).

One of my first introductions to Talbot as a new student came from a talk from one of the deans. The dean was emphasizing that over his many decades in seminary education, he had never witnessed a pastor lose their pastorate because of a theological issue (even though, he noted, we must never neglect this emphasis in our education). Rather, he knew countless stories of moral infidelity and pervasive sin that destroyed churches, families, and ministries. Talbot is a place, he emphasized, that should never forget who we are becoming, and that our ministry flows out of a life devoted to the Lord. This is one of the many reasons we must remember that ministry is not merely a performance but is a spiritual calling to minister in such a way that we shepherd people to Christ. This is a calling of a whole person — a whole life — and not merely a life of the mind. This is the call to love God with your whole heart, mind, soul, and strength, and to love your neighbor as yourself. This is the call of the spiritual theologian.

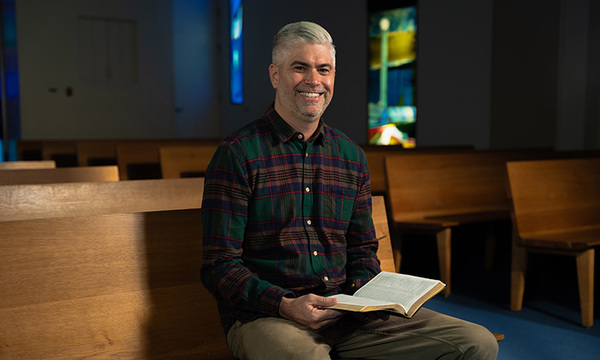

Kyle Strobel (M.A. ’02, M.A. ’05) is director of the Institute of Spiritual Formation and an associate professor of spiritual theology at Talbot School of Theology. The author of several academic and popular-level books, Strobel has a Ph.D. in systematic theology from the University of Aberdeen.

Biola University

Biola University