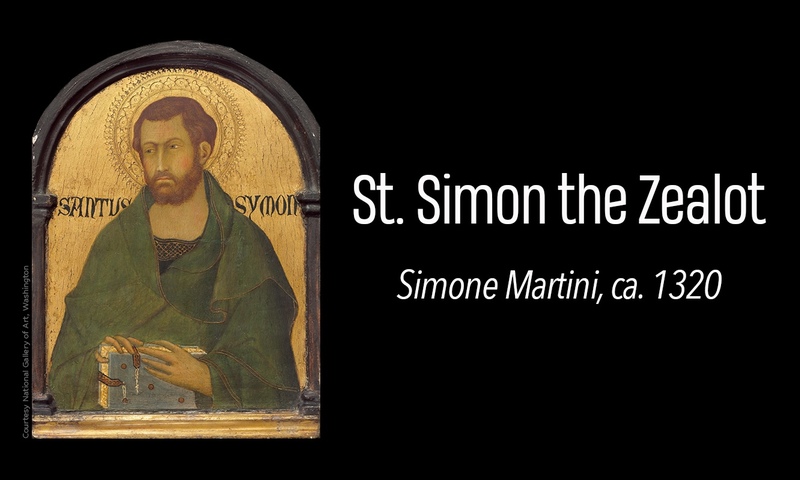

In season 2 of the popular television series The Chosen, the apostle Simon the Zealot is depicted as a former assassin from the Zealot party ÔÇö with impressive martial arts skills! This idea matches what many preachers and some commentators have said when commenting on the lists of the twelve apostles: Simon was a revolutionary who laid down his arms and became a follower of Jesus. It preaches well! [1]

But a careful read of the story of the Zealots makes it very unlikely that Simon was called ÔÇ£ZealotÔÇØ because he was a member of the Zealots. The confusion arises because modern readers think that the word ÔÇ£zealotÔÇØ means ÔÇ£rebelÔÇØ or ÔÇ£insurrectionist.ÔÇØ But this is not the case. Simon was not likely a member of the Zealots because there is no evidence that the particular rebel band called the Zealots existed until A.D. 67, and because the normal meaning of the word ÔÇ£zealotÔÇØ was positive and did not necessarily suggest violence.

The use of the Greek word ╬Â╬À╬╗˼¤ä╬▒╬», Zealots, to refer to a particular band of rebels can only be found in Josephus, the first-century Jewish historian. The word is not used to refer to a rebel band in the New Testament or in any other historical accounts. Josephus introduces them as one of many groups that were active during the Jewish War (A.D. 66-70). But Josephus never uses the term ÔÇ£ZealotÔÇØ as a synonym for ÔÇ£rebel.ÔÇØ When Josephus introduces the rebel groups who began during the reign of Archelaus (4 B.C. - A.D. 6), he calls them ¤â¤ä╬▒¤â╬╣╬▒¤â¤ä╬▒╬», insurrectionists, or ╬╗ß┐â¤â¤ä╬▒╬», bandits. He uses these terms consistently throughout his account of the various conflicts in the first century. In some cases, he identifies the names of particular groups of ¤â¤ä╬▒¤â╬╣╬▒¤â¤ä╬▒╬» or ╬╗ß┐â¤â¤ä╬▒╬». Many of the groups are referred to by the name of their leader, such as Judas, Theudas, the Egyptian, or Simon bar Giora. ╬ñhe Sicarii (Acts 21:38), named for their use of the sicarius dagger, formed during the governorship of Felix (A.D. 52-60). Another group formed in A.D. 67, during the Jewish War, and called themselves ╬Â╬À╬╗˼¤ä╬▒╬», Zealots. Josephus described them not as the entirety of the Jewish resistance, but one of several groups.

Why did this rebel group pick the name ╬Â╬À╬╗˼¤ä╬▒╬»? Well, ╬Â╬À╬╗˼¤ä╬«¤é was in general a positive word in the New Testament, the Septuagint, and in other Greek literature. It meant someone who was zealous for something, usually something good, or who was a follower or admirer of someone. Among Jewish people, it could refer to being zealous for the Law. Onias, a high priest in the second century BC, was called a ÔÇ£zealot for the LawÔÇØ because he advocated for faithfulness to the Law ÔÇö but he did not take up arms against the Greek oppressors (2 Macc 4:2). In the New Testament, the Jerusalem elders describe the church in Jerusalem as ÔÇ£zealots (╬Â╬À╬╗˼¤ä╬▒╬») for the LawÔÇØ (Acts 21:20). Paul says he is a ÔÇ£zealot (╬Â╬À╬╗˼¤ä╬«¤é) for God,ÔÇØ as are the members of the Sanhedrin (Acts 22:3), and praises the Corinthians as ÔÇ£zealots (╬Â╬À╬╗˼¤ä╬▒╬») for spiritual giftsÔÇØ (1 Cor 14:12). Peter encourages us to be ÔÇ£zealots (╬Â╬À╬╗˼¤ä╬▒╬») for goodÔÇØ (1 Pet 3:13). In Greek, ╬Â╬À╬╗˼¤ä╬«¤é functions as a noun or an adjective, so many translations choose to translate it as ÔÇ£zealousÔÇØ in these passages. (For other positive uses of ╬Â╬À╬╗˼¤ä╬«¤é, see Titus 2:14, Josephus, Life 2, War 6.59, Plut., Phoc. 4.2).

Because ╬Â╬À╬╗˼¤ä╬«¤é was such a positive term, Josephus was offended that this violent rebel group took it as their name. ÔÇ£For this they called themselves, as if being zealous in good conduct, and not in the most evil and excessive of deedsÔÇØ (War 4.161). And later ÔÇ£ÔǪ nor was there any previous villainy recorded in history that they failed zealously to emulate. And yet they took their title from their professed zeal for virtueÔǪÔÇØ (War 7.268-271). Indeed, the Zealots fought not only against the Romans but also against other resistance groups, and they brutally killed many innocent civilians.

The church fathers did not think that Simon was named ÔÇ£ZealotÔÇØ because he was a freedom fighter. As I read through the references to ÔÇ£zealotÔÇØ in the church fathers, I got the impression that the church fathers were unaware that the group existed! Only one church father, Hippolytus, even mentions them as a group; and he does not mention that they had any role in the Jewish War (All Heresies 9.21).

The church fathers clearly used zealot as a positive term. They gave the nickname the zealot not only to Simon, but also to Phineas, Elijah, Jeremiah and Paul. The church fathers sometimes emphasized the humble past of the apostles, mentioning that they were fishermen and tax collectors (Chrysostom, Hom. on Matthew 32.3). But none of the fathers suggests that any apostle had been a revolutionary. Chrysostom, referring to Pauls use of the term in Acts 22:3, said that zealot was a high encomium (Hom. on Acts 47); and that Simon the Zealot was named from his virtue (Hom. on the Betrayal of Judas 2.10-15). Ambrose of Milan connected Simons nickname with zeal for God and the zeal for your house that Jesus displayed (John 2:17; De offic. 2.30.154). Only one church father, Jerome, seemed to have connected Simons zeal with anger, but he did not suggest that Simon had been a revolutionary (Letter 109.2). This is not surprising, since the church fathers often encouraged people to be zealots for God, for godliness and for the covenant of Christ.

So how did Simon get his nickname? Since the rebel group ÔÇ£the ZealotsÔÇØ only existed from A.D. 67-70, it seems much more likely that Simon was given his nickname in accordance with the meaning of ÔÇ£zealotÔÇØ found elsewhere in the New Testament, the LXX and in the church fathers: Simon was known for being zealous for God or zealous for good things. Maybe he already had this nickname before he became a follower of Jesus, or maybe it was given to him during his time of following Jesus. [2]

Notes

[1] He is called ÔÇ£Simon the ZealotÔÇØ in LukeÔÇÖs two lists (Luke 6:14-15, Acts 1:13), but ÔÇ£Simon the CananeanÔÇØ in the apostle lists in Matthew 10:4 and Mark 3:8. ÔÇ£CananeanÔÇØ is most likely the Aramaic word for ÔÇ£zealot.ÔÇØ

[2] The claims presented here are actually well-known among NT scholars, although not held unanimously. For example, multiple articles in the Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels mention that the Zealot party did not begin until AD 66 or 67, and that Simon likely did not belong to such a group. Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels (2nd edn; IVP: 2013): 42, 409, 796, 798. See also Dictionary of New Testament Background (IVP, 2000): 586-7; Nolland, Luke 1:1-9:20 (Word Biblical Commentary, 1989): 271 and especially Horsley and Hanson, Bandits, Prophets, and Messiahs: Popular Movements in the Time of Jesus (Winston Press, 1985).

Biola University

Biola University